3 Epic Cycling Routes Chosen By Peter Cossins, Author Of Ultimate Etapes

Want a way to test your fitness and bag an epic adventure in the process? Then prepare to tackle one of these classic cycling routes

Sign up for workout ideas, training advice, reviews of the latest gear and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

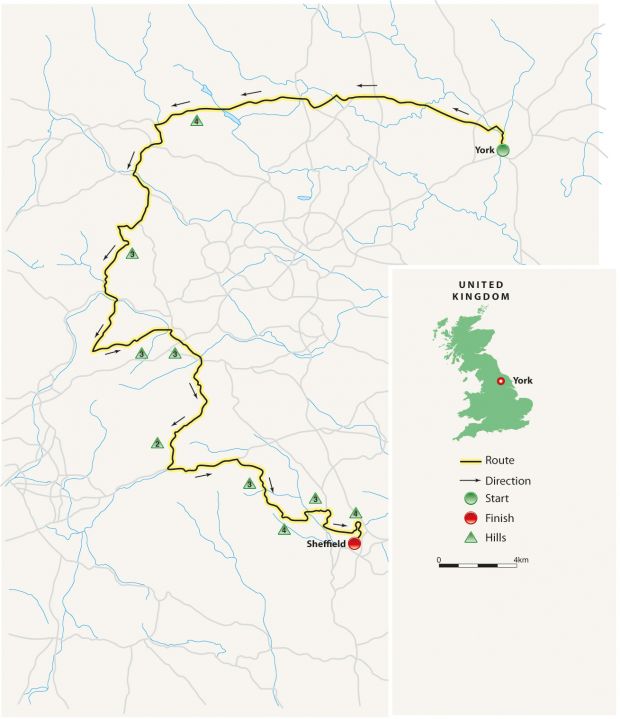

1. The Yorkshire Rollercoaster

Get a Tour de France-style test of your cycling abilities without leaving these shores in this long-distance Yorkshire classic

Route York to Sheffield, England Distance 201km

If you’d asked almost any European professional racer about England’s landscape before the 2014 Tour de France Grand Départ in Yorkshire, they would probably have referred to William Blake’s description of a “green and pleasant land” – no mountains, essentially flat roads and lots of rain. The Tour’s visit changed this perspective completely, particularly with the epic ride through North, West and South Yorkshire.

The route of the 2014 Tour’s two stages through Yorkshire is marked by brown signs, starting at York Racecourse where they point west towards the Dales. This opening section is benign, as long as the prevailing westerly wind isn’t gusting too briskly. The main road, the A59, arrows towards the affluent spa town of Harrogate and then, just beyond it, the going gets a little tougher as the road climbs onto open moorland for the first time, heading past the American listening station at Menwith Hill.

Soon after sweeping down past the turn towards Fewston Reservoir and the unforgettably named village of Blubberhouses, the road begins to ascend the first of no fewer than nine categorised climbs – those with an official difficulty rating from one to five – when the Tour riders tackled this route. Described then as the Côte de Blubberhouses, the hill is known by local riders as Kex Gill after the farm at its summit. Make the most of the long, steady descent down into Wharfedale, for once the route begins to climb away from the river – with its waters the colour of stewed tea or strong beer – the climbs keep on coming.

Cobbled together

When he was advising Welcome To Yorkshire and the Tour de France organisation on this stage, Yorkshire pro Russell Downing said of it, “There are so many ups and downs to deaden your legs, and most of them are not even categorised”. It’s at this point that this realisation begins to dawn. The first of many significant climbs that weren’t categorised when the Tour passed through is a long drag out of Addingham over Cringles and into Airedale at the small town of Silsden. The next is a widely photographed cobbled hill that climbs up through Haworth, with its renowned parsonage that was home to the Brontë sisters at the crest. Beyond Haworth, the route reaches the second of those nine Tour climbs as the road rises onto the windswept openness of Oxenhope Moor.

The B6113 speeds down into Calderdale and Hebden Bridge. This valley is narrower than Wharfedale and Airedale, with hills looming over the River Calder and the old mill towns along its banks.

Sign up for workout ideas, training advice, reviews of the latest gear and more.

Inevitably, there’s another big climb just ahead, although the rise from Cragg Vale is steady rather than steep. Surprisingly, this is another “bonus” climb rather than one of the categorised ascents – even though, at 9km, it’s the longest continuous road climb in England. Yet because it rarely ramps up beyond 5% incline, the pros flew up it.

Uphill battle

Topping Cragg Vale (and crossing into Lancashire for a few hundred metres), you’re now well past halfway. However, most of the climbing still lies ahead. This begins at Ripponden Bank, which rears up intimidatingly as the road passes the whitewashed façade of the Old Bridge Inn, home to the National Pork Pie Festival in March. The next section is the busiest and most unattractive of what is otherwise a stunning route, taking in the hill at Greetland, bypassing Elland, crossing the neverending flow of traffic on the trans-Pennine M62 and dropping into Huddersfield.

This is Brian Robinson’s former stomping ground. The first Briton to finish the Tour de France and also the first to win a stage, the Mirfield rider is now well into his eighties, but still gets out on these roads on an electric bike, although he now avoids the area’s notorious climb. Rising out of Holmfirth, Holme Moss extends to 5km and reaches 521m of elevation, the highest point on this ride. Averaging 7%, it’s not especially tough, but the weather – particularly the wind – can make it devilishly difficult, especially on its exposed upper slopes. A word of warning, too, about the descent off it towards the Woodhead Pass: it is steep with long straights and, consequently, is very fast. Unlike the pros, you won’t be tackling it on closed roads, so err towards on the side of caution.

The route follows the main Manchester-Sheffield road for a few kilometres before dipping south into the heart of the Dark Peak on the northern edge of the Peak District. Comparisons have been made between this stage and the route of the hilly Liège-Bastogne-Liège Classic, arguably the toughest one-day race on the pro calendar, and this section between Holmfirth and Sheffield is the principal reason. Known locally as the Strines, the terrain between Midhopestones and Oughtibridge dips and rises consistently and savagely. Once it has been negotiated, Sheffield finally comes into view.

Taking the rise

The original plan for the Tour’s 2014 finish in the Steel City was straightforward: the final 10km would be flat. However, Tour route director Thierry Gouvenou went exploring the hills to the north of the city centre and discovered what has become a legendary piece of cycling real estate in the shape of Jenkin Road, a residential street that rears up so precipitously that there is a handrail on the pavement. For a good distance the gradient reaches an astonishing 33%, so ridiculously steep that it’s almost laughable. It is, though, the very last time you’ll need to engage your smallest gear.

The route finishes adjacent to the English Institute of Sport and its indoor athletics arena. The surrounding landscape is industrial and functional, and hardly in keeping with the spectacular rollercoaster route negotiated to get there. But fatigue and relief will be so complete that most will be happy to reach this point, the end of one of the most exciting (and best-attended) Tour de France stages in recent history.

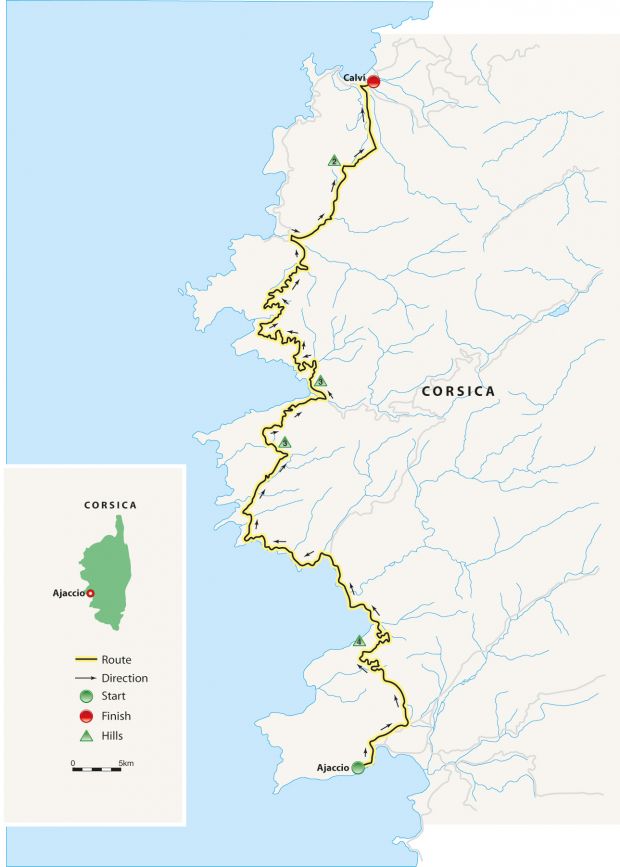

2. The Stage Of 10,000 Corners

This winding coastal route takes in the rocky outcrops of Corsica’s World Heritage Site at Calanques de Piana before a finish at the citadel of Calvi

Route Ajaccio to Calvi, France Distance 145.5km

When the itinerary of the 2013 Tour de France was announced, the race’s then route director Jean-François Pescheux couldn’t disguise his glee as he discussed the third stage between Ajaccio and Calvi on the island of Corsica. “It’s the kind of stage we’ve been looking for for years,” Pescheux revealed. “There’s not a single metre of flat, which means the peloton will get very stretched out, presenting the real possibility of splits occurring – especially as, at 145km, this stage is very short.”

Pescheux and Tour director Christian Prudhomme had twin goals by starting the 2013 race on the French island. Most importantly, the three stages were the first ever to take place in Corsica, which had not previously been a viable venue as a result of long-standing concerns about possible terrorist attacks by local nationalists seeking independence from France. The fact that the Tour’s management picked the 100th edition of the Tour to end this exile, thereby ensuring that the Tour had visited every one of France’s domestic départements, only underlined its meaning.

Flat out

Corsica’s rugged terrain also presented Pescheux and Prudhomme with an ideal opportunity to add some spice to the Tour’s opening trio of stages. Running up the east side of the island, stage one was essentially flat, allowing the peloton’s sprinters to lead a stampede into Bastia, ultimately headed by Germany’s Marcel Kittel. Stage two crossed the island, rising to more than 1,000m on the Col de Vizzavona, before a complicated finish in Ajaccio as Belgium’s Jan Bakelants crossed the line a second ahead of Slovakian Peter Sagan. The third stage, running up the northwest coast of Corsica, rolled and twisted incessantly, taking in some of the island’s most spectacular scenery before the finish in Calvi, where Australia’s Simon Gerrans edged out Sagan for victory.

This third stage started in Ajaccio, which with its airport, ferry terminal, good road connections and plentiful hotels is the ideal base for two-wheeled escapades. It’s rather beautiful, too.

There is almost no need to worry about getting lost on this route, either. After leaving the centre of Ajaccio on the main N194, the road passes a shopping centre on the city’s outskirts and then continues for another kilometre to a roundabout and swings left onto the D81, which it follows for the next 140km to Calvi.

Already rising as it moves away from Ajaccio, the road climbs a little more steeply into a rocky landscape, crossing the Col de Listincone. After a brief drop, the road soon ramps up again for the bigger Col de San Bastiano, which was rated a Category 4 ascent for the Tour’s stars. Over to the west, views across the sea become more impressive with each metre of altitude gained.

Natural wonder

Beyond the little chapel at the top of the pass, the road drops back down to sea level to loop around the lovely bay at Tiuccia. Its beauty is enhanced by the relative lack of development, a feature the Corsican people have been fiercely determined to maintain. What buildings have been permitted are low-rise and as unobtrusive as possible.

This stretch is the easiest on the route. Passing Sagone and sweeping around the upper side of the huge bay that takes its name from that little town, the road is essentially flat. It bumps up a little to reach Cargèse, its little harbour and beach tucked in behind the protective arm of a breakwater below. North of Cargèse, the road, which has hitherto hardly been blessed with many straights, begins to wiggle even more frenetically, rising into rugged hills covered with scrubby vegetation to the San Martino pass and on into the small town of Piana.

Beyond this village lies one of the most dramatic sections of coastal road anywhere in Europe. Well above 400m, it looks down into the Calanques de Piana, narrow and steep-walled inlets cut by the sea from the pinkish limestone, which turns to bright hues of red as the sun begins to set. The first hint that something extraordinary lies ahead comes a few kilometres above Piana, when the road emerges from a tight left-hander onto a “balcony” section. A couple more turns further on, this balcony effect becomes much more pronounced when the road runs along a ledge hacked from the cliff face. If this balustrade-less stretch twisting around bend after bend doesn’t slow you down, the views will.

Round the bend

Weaving between crumbling pinnacles of rock, the road emerges into a much greener landscape, the hills now thickly wooded. By now it’s clear why this was dubbed “The Stage Of 10,000 Corners”. One curve leads almost instantly into the next, dropping into Porto, where a bakery on the far side of the viaduct over the end of the jaw-dropping Spelunca gorge provides a convenient refreshment point.

The section that follows is arguably more spectacular still, as the road climbs on a ledge high above the Gulf of Porto, headlands rippling in the distance. Topping the Col de la Croix, which didn’t merit categorisation by the Tour, the route then edges inland. Although it leaves the sea behind for the time being, it zigs and zags no less furiously as it ascends another uncategorised climb, the Col de Palmarella, which marks the border between Corsica’s two départements.

Over the next 10km the road angles down gently to the scrubby Fango and Marsolino valleys, their courses mostly pebbles in the summer months after the mountain snows have melted. The route follows the Marsolino for half a dozen kilometres before starting up the pass of the same name. This col is quite different to the earlier ones, the road sweeping up in broad curves above the wide valley, then dropping down the far side in the same fashion.

The road to Calvi

As it takes you into Calvi, the road runs with hardly a deviation until it passes the tiny airport. Rather than continue into the port, it turns right onto the N197, then again onto the D151 to finish on the other side of the runway on a dusty and nondescript road. It is next to the headquarters of the French Foreign Legion’s 2nd Parachute Regiment, which was clearly chosen to accommodate the Tour’s immense convoy of vehicles and other paraphernalia.

However, without that massive logistical concern to worry about, a better alternative is to continue directly into Calvi, where the citadel jutting proudly into the sea offers a finale more appropriate to the spectacle laid on before.

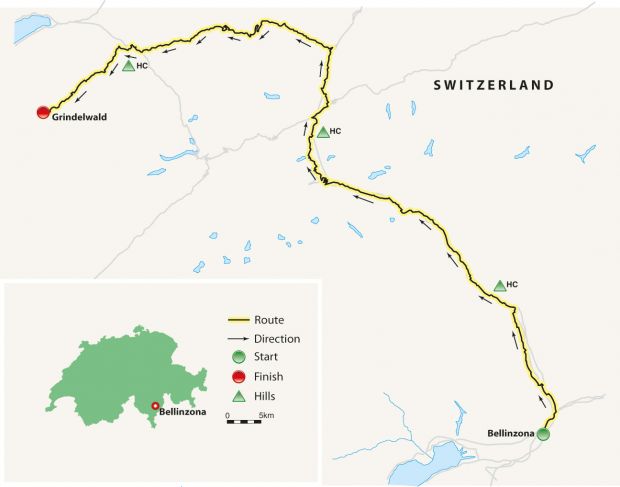

3. To The Foot Of The Eiger

Have your breath snatched away by this mountain epic that takes you through the foothills of the Swiss Alps

Route Bellinzona to Grindelwald, Switzerland Distance 171.4km

The beauty of riding in the Swiss mountains is that most of the roads appear to have been designed with the cyclist in mind. Although many of them soar to altitudes in excess of 2,000m, they generally do so in comparatively leisurely style, sweeping upwards in huge, extravagant curves and suggesting that Swiss road engineers consider a gradient greater than 10% vulgar and unnecessary – something they would prefer to leave to their counterparts over the border in France, Austria and, above all, Italy. Taken from the 1999 edition of the Tour de Suisse, this route emphasises both the elegance of this approach and the way in which it can tempt riders of all abilities onto some of the Europe’s highest roads, encouraging access rather than laying down a challenge.

It begins in the spectacular setting of Bellinzona, capital of the Italian-speaking Swiss canton of Ticino. Lying a few kilometres from the northern extent of Lake Maggiore, Bellinzona holds World Heritage Site status thanks to the Castelgrande, Montebello and Sasso Corbaro castles, which dominate the town. Setting out from the northern side of the Castelgrande, the ride tracks the River Ticino on route 2. This can be busy in rush hour, although the nearby A2/E35 motorway, which also tracks the Ticino, sucks up most of the traffic.

At Biasca the route, which has been rising almost indiscernibly since the start, forks left into a narrower valley where the Ticino, the motorway, the main railway line and our course get squeezed in more tightly together. Just beyond Giornico, the river begins to flow with urgency, signalling an increase in the gradient on what is now the Via San Gottardo, the first step towards the fabled San Gottardo/St Gotthard Pass. Approaching the climb, the motorway and railway keep vanishing into tunnels. At Airolo, they disappear altogether, boring through the mountain for 17km.

Blind turns

A main road continues over the pass, but don’t make the mistake of following the road traffic because you will miss one of the most astonishing sections of road in Europe. At the foot of the climb, a sign diverts cyclists off to the right onto the Via Tremola, which winds to the 2,091m summit via 38 hairpins. Stacked up one on top of the next, like the folds of a drawn curtain, the bends instantly capture the eye. However, the wonder of the St Gotthard Pass is not these swirling switchbacks but the road’s surface, which is cobbled all the way to the summit.

Built in the first half of the 19th century to ease passage through one of the most important trade routes in the Alps, the Via Tremola was superseded initially by the main road and then by the motorway tunnelled through the mountain. But the traffic innovations have been to the benefit of the old road: sections that had been covered with Tarmac have been restored, and the flat-topped cobbles renovated or replaced. The result is a unique and totally glorious experience, far smoother than the cobbled Classics in northern Europe. Brilliant engineering also extends to the gradient, which remains at 7-9% apart from one short section 3km from the top, when it briefly rises above 11%.

Climbing towards the pass, the curving patterns of the cobbles and the grass between the stones cause the road to almost blend in with the rocky landscape and scree fields, suggesting that nature has somehow laid this perfect trail. Beyond the Lago della Piazza at the top, with its handful of hotels and restaurants, the cobbles continue for 3km along the Strada Vecchia before the old and new roads combine as they enter the German-speaking canton of Uri on the descent towards Hospental.

This tidy village overlooked by a crumbling 13th-century tower offers a wealth of delights to mountain lovers. A turn to the west leads to the Furkapass, while the route north leads quickly to Andermatt, at the foot of the Oberalppass. Continuing towards Göschenen, the road dives into the Schöllenen Gorge, a precipitous cleft where the Teufelsbrücke (Devil’s Bridge) leaps across the rushing Reuss. Legend has it that construction of the original bridge was so tough that the Devil offered to complete it in exchange for the soul of the first being to cross it. The locals agreed but chased a goat across the finished bridge, angering the Devil, who returned to destroy it, only to be thwarted by a woman brandishing a cross.

At Göschenen, the motorway and railway emerge from the St Gotthard tunnel and run alongside the route as far as Wassen, where your turn northwest onto the first ramps of the Susten Pass. At almost 18km, this is the longest ascent on the route. It’s consistently demanding and, particularly over the final half-dozen kilometres, breathtaking in both senses of the word.

Peak performance

After the long drop from the top of the St Gotthard, it’s a shock for the legs to be climbing again, and quite steeply too, on the road out of Wassen. But this is quite different mountain scenery to the St Gotthard. Tracking up the northern flank of the valley above the waters of the Meienreuss, it follows a straight course running directly towards the Wendelhorn and the Fünffingerstöck, with its five jagged peaks.

The head of the pass is visible from some distance away, which can be daunting because progress towards it is not rapid – but the scenery is fabulous, with more peaks and glaciers appearing. Beyond 2,000m, the road switches southwest towards the Stein Glacier and soon reaches the short tunnel at the summit that leads through into the canton of Berne and on to the close-to-30km descent into Innertkirchen.

Built over seven years up to 1945, the Susten Pass was the first in Switzerland created purely for road traffic rather than following a long-established trading and travel route. Thanks to this, it’s beautifully surfaced and engineered. After a few hairpins just below the summit, it flows like a giant slalom course down the mountain. There are long straights and most of the corners are so well cambered that the brakes need merely a touch. Professionals have been known to achieve speeds in excess of 110km/h on these slopes (bear in mind that’s on closed roads).

The route continues towards Meiringen, veering left before the town towards the Grosse Scheidegg. This is another long and quite gruelling climb, so it could well be time for a break. Just a few metres up the climb, there’s an ideal spot for a rest in the form of the Reichenbach Falls. Renowned as the location of the final confrontation between Sherlock Holmes and his arch-enemy, Professor Moriarty, the falls have a combined drop of 250m, the awe-inspiring plunge of the Upper Reichenbach alone accounting for more than a third of that.

Sound of silence

Back in the saddle, the narrow road climbs alongside the cascading River Reichenbach through thick woodland and past occasional farms. Thanks to a bar on all motor traffic except postal and farm vehicles, it is wonderfully quiet. The lack of traffic does mean the road surface is not as well maintained as the Susten’s, but this isn’t a critical issue going upwards.

As you emerge from the trees and onto an easier gradient, the Schwarzenwaldalp is dead ahead, its lower peak half-concealing the upper part of the mountain as the Rosenlaui Glacier hangs over its shoulder. The road steps to a slightly higher level and passes the Hotel Rosenlaui, before kicking up again for the final run to the summit. Much of the next 7km is wickedly steep.

After one final wooded section, the route ventures into lush mountain meadows, running parallel to the course of the Reichenbach towards the cliffs on the south of the valley. Approaching the summit, the peaks on the other side of the pass loom into view, including the Eiger, its infamous North Face almost permanently in shadow.

Once over the top of the Grosse Scheidegg, the route down is steep but short. Within half an hour you can be sipping a beer in a Grindelwald café and making a start on replenishing your carb levels, all while taking in one of the most world’s most celebrated mountain vistas.

Ultimate Etapes: Ride Europe’s Greatest Cycling Stages by Peter Cossins (RRP £20, Aurum Press) is out now, buy on amazon.co.uk

Coach is a health and fitness title. This byline is used for posting sponsored content, book extracts and the like. It is also used as a placeholder for articles published a long time ago when the original author is unclear. You can find out more about this publication and find the contact details of the editorial team on the About Us page.