The Self-Transcendence 3100 Mile Race: A Long Distance Love Affair

Some of the world’s best ultrarunners will gather in Queens, New York on June 19 to run around a single city block. For 3,100 miles

Sign up for workout ideas, training advice, reviews of the latest gear and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Imagine running a marathon. Then another. And, for kicks, finishing with a seven-mile jog. On the same day. Sounds ridiculous, right? Now imagine doing it all again the next day. And the one after that. In fact, for 52 days in a row.

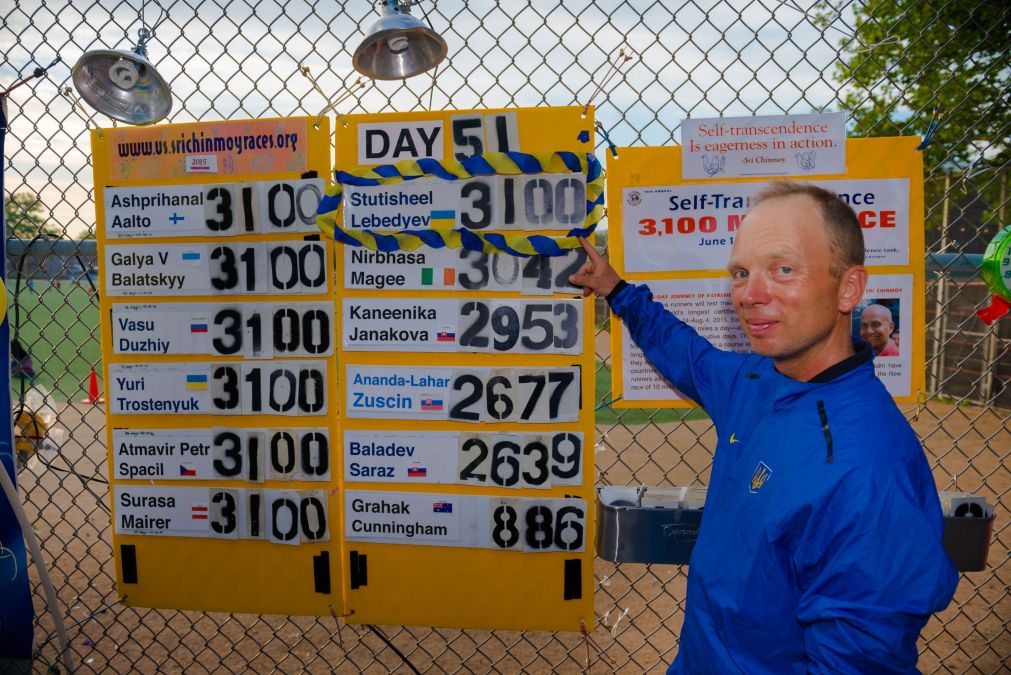

That, in essence, is what the annual Self-Transcendence 3100 mile race demands of anyone brave – or barmy – enough to take on the world’s longest certified ultra-running race. Yet every year a dozen or so athletes allow their bodies and minds to be put through the wringer.

Their goal is simple enough. To complete 3,100 miles in 52 days or less – an average of 59.6 miles a day. That, though, is only the start. They also have to face the raging heat and stifling humidity of a New York summer. The blisters, shin splints and aches in places they never knew existed. And being almost constantly on the move between 6am and midnight – yet also having to find a way to consume between 7,000 and 10,000 calories a day without suffering the world’s most epic stitch.

Most athletes find they wear out between 10 and 15 pairs of shoes and that their feet swell an extra two sizes. And usually there is something else that creeps up on them, too. A gradual realisation, as they embark on what might be their hundredth or even 150th lap of the day around the loopy 883m (a little over half-a-mile) course in Jamaica, Queens, that their body isn’t the only thing going around the bend.

“I almost was on the verge of a mental breakdown at one point,” admits William Sichel, a British ultrarunner who has set multiple world records but had to draw upon all his powers to complete the race in 2014. “The busy pavements got to me. So did the temperatures pushing 100 degrees Fahrenheit, the 95% humidity, and noise. It never stopped. There was this 12-lane highway near the long straight of the course, so it was hard to be alone with your thoughts and get into the zone.”

The 62-year-old Sichel, who became the oldest man ever to finish, got through by breaking each day into manageable chunks. Sixteen laps before 8am. Forty laps by noon. Seventy by 5pm. Then pushing 120 by midnight when the race was called off for the night. He would also repeat the phrase, “I can do this” and remind himself of the money he was raising for charity. Others, though, have found it all too much.

Sahishnu Szczesiul, the associate race director, chuckles as he tells Coach about one particularly confident German athlete who had finished third or fourth in a race across America and felt the Self-Transcendence 3100 mile race would be a breeze. “He ran 70 miles every day at the start, and I saw him telling people, ‘this is very easy for me’,” says Szczesiul. “Then there was a heatwave, and the reality of the race set in. Within a week he pulled out and hired a car to drive to Las Vegas with his girlfriend.”

Sign up for workout ideas, training advice, reviews of the latest gear and more.

The race celebrates its 20th anniversary in June and is the brainchild of Sri Chinmoy, an Indian meditational guru who believed that running long distances could exemplify the endless possibilities of the human spirit. Because of its psychological and physical demands, it is invite only. Between 12 and 14 ultrarunners, mostly men, do it each year – each paying the entry fee of $1,250 (£858), a not unreasonable sum given accommodation – two to a room – and food (always vegetarian) is provided.

Accommodation is basic but functional, and many athletes learn to wake and run again after just four or five hours of sleep a night.

“When we started in 1997, the neighbourhood was very different,” admits Szczesiul. “Two days before the first race, a car had been pilfered and set alight and it was still smouldering when we started. There were also people selling drugs across the street. But over the years, the area has become gentrified so it is an amazing mix now.”

That said, the runners still have to swerve around local school kids in the morning and afternoon, and Sichel says the locals aren’t always entirely friendly. “We were lectured before the race never to push anyone out of the way because it will cause a riot,” he says, chuckling. “I could see why, but there were times you felt like lashing out.

“I also saw some people the same time every day for 50 days and they sort of blanked me for 50 days,” he says laughing. “It’s just how people are there. But there were never any security concerns and the people who set up the race are amazing – they do everything to help.”

Each year, organisers rent a double garage a mile from the course and convert it into a kitchen, where a half-a-dozen or so of the 100 volunteers involved in the race make food for the runners. They also set up rows of camper vans by the course so athletes can rest, or briefly sleep, during the day. Not many of them do so for long. Sichel learned to eat tiny amounts every 30 minutes while running – including ice cream and double cream – to fuel himself, and restricted himself to a short break in the morning and a sleep of between 45 minutes and 90 minutes in the afternoon.

“I learned to eat in very small quantities regularly, because that’s what the old hands did,” he says. “It helped when my friend Adrian Tarit Stott flew out after two weeks because I wasn’t having to stop to cut up my food or get drinks. Without that I wouldn’t have finished the race.”

Sichel rapidly picked up other tips, too. “I had all sorts of ultra-distance records but within the first few hours of doing the race, I realised I was an absolute novice,” he admits. Sichel’s initial plan had been to run for 10 minutes then walk for 10 minutes. After a while, though, he found even the modest slopes on the course “becoming like Mount Everest”. Instead he copied everyone else – and developed a trotting style, which saved his energy, while walking up slopes and running down them.

“If the guys I raced against entered a normal race like a marathon, or even a 24-hour or six-day race, I wouldn’t even see them, because they’d be at the back of the pack,” explains Sichel. “But over this insane 3,100-mile race they were absolute supreme specialists.”

Last year’s winner, Ashprihanal Aalto – whose day job as a courier in Finland allows him to train while he works – took just 40 days and nine hours to complete the 3,100 miles, averaging 76.7 miles a day. That victory, his eighth in total, smashed the course record by nearly a day. He never slept more than four hours and 45 minutes a night, and only took three 12-15-minute breaks every day where he learned to fall asleep almost instantly so that he could power nap for 10 minutes in a camper van.

Not that he was entirely virtuous. Sometimes he would occasionally eat crisps while running. Others prefer to just take liquids and foods that have been blended during the day, and eat like kings at midnight. “I’ve seen people come off the course at the end of the day having barely eaten for 18 hours, and grab four huge bowls of grains and vegetables mixed with rice and wolf down as much as possible,” says Szczesiul. “And then they head off to a nearby apartment, shower and sleep for a few hours and return at 5.45am. Towards the end, some athletes need five or six alarms to wake them up.”

Szczesiul says that runners also have to learn to enjoy the endless process of run, eat, sleep, repeat, while ignoring the pain and repetitive strain of running the same stretch of road 5,649 times in a row.

Those who survive are rewarded with a T-shirt and plastic trophy. It’s not much, but those who take on Self-Transcendence 3100 mile race aren’t really interested in enriching their pockets, but their bodies and minds.